This modest, albeit gruesome excerpt from the exhaustively footnoted Equal Justice Initiative’s Report requires no contextualizing for current relevancy, as it speaks entirely on its own to the shared cultural history of modern Southerners, who include black compatriots that are descendants of slaves and Jim Crow survivors.

Every persistently unacknowledged aspect and shameful chapter of that ostensibly inviolable cultural history is presently enshrined in State-consecrated monuments to iconic defenders of the vanquished Confederacy; but they popularly commemorate its subsequent pogroms of racial subjugation.

As to what lies below, I will only preface it by saying:

Please deliver me unto the tender mercies of an ISIS beheading blade and I will smile for the camera. Only, I beg you. Spare me from a three-ring circus of bible-belt grindhouse horrors at the hands of noble Christian sons-o’-the-south; feral-Protestant torture porn, which no droning calliope choruses of ‘yes, buts’ and ‘whatabouts’ will ever mitigate.

[Bracketed passages are my few additions from a local source.]

PUBLIC SPECTACLE LYNCHINGS

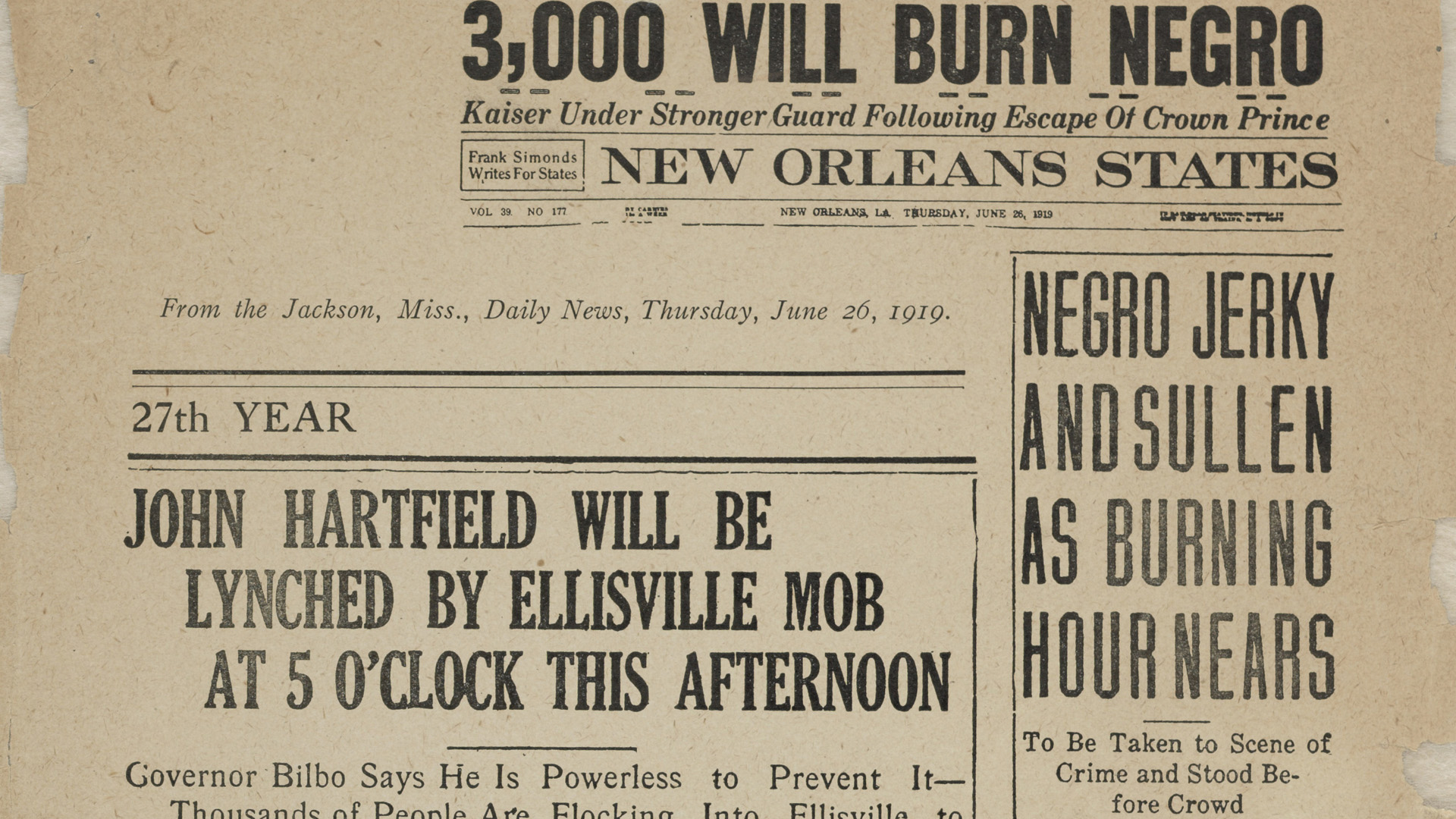

Public spectacle lynchings were those in which large crowds of white people, often numbering in the thousands, gathered to witness pre-planned, heinous killings that featured prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and/or burning of the victim.160

Many were carnival-like events, with vendors selling food, printers producing postcards featuring photographs of the lynching and corpse, and the victim’s body parts collected as souvenirs.

In 1904, after Luther Holbert allegedly killed a local white landowner, he and a black woman believed to be his wife were captured by a mob and taken to Doddsville, Mississippi, to be lynched before hundreds of white spectators.162 Both victims were tied to a tree and forced to hold out their hands while members of the mob methodically chopped off their fingers and distributed them as souvenirs. Next, their ears were cut off. Mr. Holbert was then beaten so severely that his skull was fractured and one of his eyes was left hanging from its socket. Members of the mob used a large corkscrew to bore holes into the victims’ bodies and pull out large chunks of “quivering flesh,” after which both victims were thrown onto a raging fire and burned. The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific murders while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere.163

Another public spectacle lynching took place in 1917 in Memphis, Tennessee, when a mob of twenty-five men seized Ell Persons from a train that was transporting him to stand trial for the rape and decapitation of a 16-year-old white girl named Antoinette Rappel. The mob had announced the lynching time and location in advance, [local papers announced he would be burned the next morning] and thousands of people attended, backing up traffic for miles. Food and gum vendors sold their wares to the many spectators as Mr. Persons was doused with gasoline and set on fire. A ten-year-old black child was forced to sit next to the fire and watch him die. When members of the crowd complained that Mr. Persons would die too quickly if burned, the fire was extinguished, and attendees fought over Mr. Person’s clothes and remnants of the rope to keep as mementos. Two men cut off his ears for souvenirs, after which the head of Mr. Person’s corpse was removed [then photographed to later reproduce on postcards] and thrown into a crowd in Memphis’ black commercial district [Beale Street].164

[‘The NAACP sent James Weldon Johnson, the writer, educator, lawyer, and civil rights activist, to Memphis as a field secretary to investigate Persons’ death. After spending 10 days in the city, talking with reporters, law enforcement officials, and locals, Johnson found there was no evidence suggesting Persons was guilty of Antoinette Rappel’s murder. Suspicion had fallen quickly on Persons, who lived near the site of the murder. He was arrested twice, interrogated twice, and released twice before being captured a third time and reportedly beaten into a confession.’]

Later that year, just a few hours away in Dyersburg, Tennessee, Lation Scott was subjected to a brutal and prolonged lynching after being accused of “criminal assault.” Thousands gathered near a vacant lot across the street from the downtown courthouse and children sat atop their parents’ shoulders to get a better view as Mr. Scott’s clothes and skin were ripped off with knives.

A mob tortured Lation Scott with a hot poker iron, gouging out his eyes, shoving the hot poker down his throat and pressing it all over his body before castrating him and burning him alive over a slow fire. Mr. Scott’s torturous killing lasted more than three hours.165

Gruesome public spectacle lynchings traumatized the African American community. The crowds of hundreds or thousands of white people attending as participants or spectators included elected officials and prominent citizens; white press coverage regularly defended the lynchings as justified; and cursory investigations rarely led to identifications of lynch mob members, much less prosecutions. White men, women, and children fought over bloodied ropes, clothing, and body parts, and proudly displayed these “souvenirs” with no fear of punishment. 166

These killings were not the actions of a few marginalized vigilantes or extremists; they were bold, public acts that implicated the entire community and sent a clear message that African Americans were less than human, their subjugation was to be achieved through any means necessary, and whites who undertook the duty of carrying out lynchings would face no legal repercussions.

Okay. Now that I’m done with the heavy artillery, feel free to re-collect yourself while I cool things down a bit with a smaller caliber appeal.

In an earlier post, I presented Billie Holliday’s penetrating rendition of “Strange Fruit,” composed in the late 1930’s.

That song’s message is neither preached nor taught, but is revealed through the feelings it evokes in conjunction with a heartbreaking, ambient soundscape into which the narrative of the words is embedded. That plaintive symbiosis lends an almost cinematic quality to the performance. Surrender yourself and within time you begin to see the details your imagination is projecting. You begin to feel the panorama of pain; of terror; of futility. Of malice and inhuman deliberation – begetting incalculable violence. Sense the blood and the sweat and the tears – the treasure of human souls – expended in this uniquely Sapiens primal ritual of Hate, that ultimately elicits an overwhelming sadness that we have learned to ignore, or have simply forgotten. And that shame that you feel is nowhere in the song itself. It is in you!

‘Strange Fruit’ certainly deserves inclusion on every “Southern Heritage” playlist; right up there with ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ and ‘Sweet Home Alabama.’

Now, ………… about those goddamn monuments…………